It’s been a very very busy 10 days since the NicsFight campaign kicked off. For those of you who don’t know, my very good friend Nic died in October from cancer; his insurance company (Friends Life) have been refusing to pay out on a critical illness policy which would transform the lives of the widow and twins he leaves behind, over a silly technicality to do with pins and needles. You can catch up on how it developed, and the huge support it has garnered by browsing the Storify page.

The whole campaign has, in amongst the whirlwind, given me pause for thought about possible links with the rest-of-my-life-as-was, and, indeed, links with the work that Nic and I did together as we talked over issues while he was still alive. I wanted to cover a few of those things, if only for my own personal archiving of thoughts.

The tens of thousands of people who have signed the petition asking Friends Life to do the right thing express to me a fundamental principle here: the spirit of the law says that Nic’s family should be paid in this case, even if the finest letter of it says that they shouldn’t. (In fact, this finest letter as a loophole for companies to avoid paying out is being changed in revised legislation coming into force in March – legislation which would likely have meant Nic being paid in full.) As I noted a day or so ago: what this boils down to is ‘the computer says no,’ vs. ‘the people say yes.’ The computer has no empathy, no spirit. And this is what has been lost in the drive to extract greater and greater profits from insurance companies by the hedge funds that have recently acquired them. Even the industry magazines sound a note of warning:

“I have been slightly concerned for years now about how claims are being tightened up mainly because of the price wars. There are some claims rejected now that could very well have been paid a few years ago.”

Friends Life began as a movement of Quakers who wanted to put in place protection for those left vulnerable by the death of a bread-winner. To use the terms used in my recent book Mutiny, ‘a commons.’ (The book was dedicated to Nic, and inspired a great deal by conversations we’d had.) That is to say, a pooling of resources by a community of people to help out any who might need it. None of us can be certain who will, so all pay in, hoping never to have to claim, but happy to support those whose suffering is relieved when they need to claim.

My firm belief is that if it were possible to poll those who paid money into the funds from which Nic’s claim would be made, a vast majority would support paying out. This is what the huge petition numbers suggest. But the commons has been privatised and enclosed. It no longer exists primarily for the benefit of claimants, but to create profits for the fund managers. This, in my view is wrong. It is a tragic move away from the communal spirit of shared-risk finance.

It is this act of enclosing the commons, privatising it for the benefit of the wealthy merchants, casting the commoners from the land that supported them, that forms the backdrop to the whole argument of Mutiny. Having had a world which was almost entirely lived in and amongst various commons, we now live in a world where virtually every commons is gone. Profits and private ownership rule, and we are told that this is most efficient way to run things in a market-driven capitalist society. Yet, as I try to show in the book, this enclosure of the commons leads to a diminishing of community bonds and the growth of hierarchies, tyrannical power structures and authoritarian, legalistic religion.

What I also try to show is that wherever we see the commons under threat, pirates rise up to beat down the enclosures and break it open again. It took me about a week to realise this, but NicsFight has been just such a classic act of piracy. It is a Mutiny waged on a corporation who have plentiful bounty that they are refusing to share.

If you read the book, you’ll see how pirates function with a ‘TAZ’ mentality: creating temporary spaces that are light and manoeuvreable. Chasing pirates was, to quote one British navy admirable, ‘like sending a cow after a hare.’ Using Twitter, Storify, Change.org, WordPress and Facebook we have very quickly been able to construct huge campaigning tools which can scale up very very easily. This has been very important. What has been quite clear from Friends Life’s end is that they simply have no idea how to use these social media tools. The three bland tweets they put out, and no other communications, are evidence of this.

But there is something deeper here. At the root of the pirate spirit is not a desire to steal or plunder – this is very very fundamental to understand. The pirate is the brutalised sailor who has had enough of unfair and unjust treatment by merchant and government ships. The act of mutiny is not one of retaliatory violence, but of breaking for freedom and self-determination. Pirate ships were early-adopters of radical democracy, electing their officials, sharing goods equally and defending the rights of all regardless of gender, race or status.

This mutiny that NicsFight has become could, I suspect, be part of a wider current of dissatisfaction with corporate greed and abuse, and the beginning of the return to a new mutualism. What I would be unsurprised to see is people withdrawing their funds from bloated insurance companies whose primary purpose is to make executives super-rich, and putting them into new forms of mutualised finance, which are a return to the spirit of the ‘commons’ – where all pay in to support those who are unfortunate to have to claim.

There will be plenty other thoughts to come too, I’m sure, and I’ll perhaps blog more about them as they come. But I wanted to lay down a marker here: NicsFight is a personal battle for one family, but its popularity is clear evidence of a far deeper and wider unrest. And it is to this unrest that I think people need to act to bring about new forms of mutual finance. A few made cosy windfalls when building societies turned into banks. This, I think we are beginning to see, was a huge mistake. It’s time to return to a financial commons.

Comments

8 responses to “Insurance as Commons, Campaigns as Mutiny: Reflections on #NicsFight”

Interesting thoughts. I have signed the petition, emailed Friends Life, but still have a Friends Life policy (linked to my mortgage) that I need to cancel and replace. I gave Friends Life a few days grace to fix the mess, but they are evidently incapable. Not only are they morally bankrupt, but they are just plain incompetent, and woefully unprepared to respond to social media. The fat cats on the Friends Life Board aren’t doing much to justify their cream at the moment.

However, as I look to replace my Friends Life policy, this post strikes a pertinent note. What do I replace it with? Do I just replace one set of greedy swindlers with another? Maybe an outcome from this campaign could be some facility to direct the financially uninformed (that’s me) in the direction of alternative providers?

The other area that has had unexpected negative impacts was the right to buy council houses in the Thatcher years. Social housing was based on a sort of Commons – we all pay taxes, some of those go to support those who find themselves in need of housing. It’s “them” now, one day it could be “us”. No big deal, and part of an effective social contract. With the right to buy, swathes of social housing were taken out of the contract and those who made money moved out, seemingly solving a problem. The effect though, was to help fuel price escalation, reduce social housing stock and exclude all but those with family money or a very well-paid job from the first time buyers market. We’re learning that the free market can provide many things, but often not freedom.

“Just a minute… just a minute. Now, hold on, Mr. Potter. You’re right when you say my father was no businessman. I know that. Why he ever started this cheap, penny-ante Building and Loan, I’ll never know. But neither you nor anyone else can say anything against his character, because his whole life was… why, in the 25 years since he and his brother, Uncle Billy, started this thing, he never once thought of himself. Isn’t that right, Uncle Billy? He didn’t save enough money to send Harry away to college, let alone me. But he did help a few people get out of your slums, Mr. Potter, and what’s wrong with that? Why… here, you’re all businessmen here. Doesn’t it make them better citizens? Doesn’t it make them better customers? You… you said… what’d you say a minute ago? They had to wait and save their money before they even ought to think of a decent home. Wait? Wait for what? Until their children grow up and leave them? Until they’re so old and broken down that they… Do you know how long it takes a working man to save $5,000? Just remember this, Mr. Potter, that this rabble you’re talking about… they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community. Well, is it too much to have them work and pay and live and die in a couple of decent rooms and a bath? Anyway, my father didn’t think so. People were human beings to him. But to you, a warped, frustrated old man, they’re cattle. Well in my book, my father died a much richer man than you’ll ever be!” George Bailey/ Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life

i like this a lot kester, especially the language of ‘commons’. it articulates something i’ve been thinking about a lot in the last few years. michael’s comment about council housing is also exactly pertinent to my thinking. there will be a blog entry eventually.

Amen, amen and amen.

and those who are shareholders – making a profit out of doing nothing are part of the problem…. as is the whole interest economy, pensions etc… do the new pirates need to let go of the whole system of economical security?

In a word, yes. Painful and enormously radical thing to do…but great freedoms on the other side I think.

A couple of things come to mind while reading both the article and the responses:

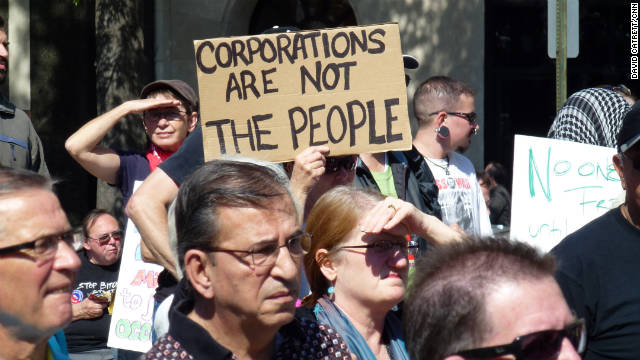

If “corporations are not (the) people”, can they be taxed as if they were?

If we get rid of shareholders, should we not also refuse their previous investments?