Tweeted about this piece earlier today, but wanted to flag up and reflect further on Henry Marsh’s piece in Granta, detailing his neurosurgical work operating on a tumour in a pineal gland.

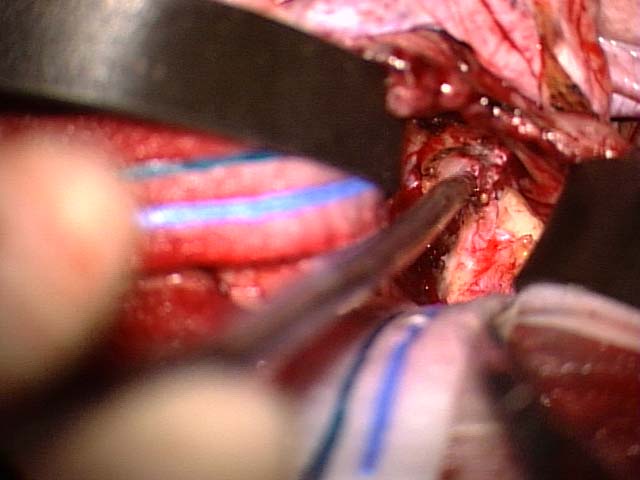

The pineal gland is buried deep within the brain, and is thus only reached after a perilous journey through the physical matter that somehow is the seat of all their memories and thoughts. As Marsh puts it:

The idea that I am cutting and pushing through thought itself, that memories, dreams and reflections should have the consistency of soft white jelly, is simply too strange to understand and all I can see in front of me is matter. Nevertheless, I know that if I stray into the wrong area, into what neurosurgeons call eloquent brain, I will be faced with a damaged and disabled patient afterwards.

Tragically, an operation he had done the week before had left a woman paralysed down one side of her body, and the beauty of this piece is the skill with which Marsh describes the emotions and stresses he feels as he goes into the next operation, with all the risks that that entails of becoming ‘another headstone in that cemetery which the French surgeon Leriche once said all surgeons carry within themselves.’

I wanted to post about this piece though, because it linked with a piece Peter Rollins wrote the other day about ‘Love, Loss and the Uncoupling of our World,’ in which he mentions Descartes’ postulation that the pineal gland was the place where the mind/body/spirit all combined.

I’ll leave you to read and reflect on that, but the third dimension to this was the fantastic novel I read over the summer The Echo Maker by Richard Powers. It details the rare – but very real – Capgras Syndrome, in which a patient wakes following some brain trauma to believe that those around them are imposters. They know that they look and speak exactly like their ‘real’ friends and relatives, but are convinced that this is just an elaborate and highly skilled impersonation.

What Powers does so well is to take us, via a great plot, inside the strange world of identity and brain function. Powers’ protagonists – the victim, his sister and the neurologist who tries to treat him – all experience dramatic fluidity in their identities, all experience dramatic ‘loss and uncoupling’ in their worlds, but all for very different reasons.

These three pieces – a memoir, a novel and a work of philosophy – have all found some resonance together with me today, reflecting on the ever-evolving question who the hell am I?

Descartes wasn’t right: the pineal gland is not the centre where mind, body and spirit collide and collude. Yet neither was he entirely wrong, because our sense of identity is not extra-physical. Our brain matter matters. And yet, as Powers and Rollins unpack in their own ways, the mystery of identity has elements which go beyond the physical into the emotional, the circumstantial, the philosophical and the spiritual (though, as Powers’ book shows, that does not necessarily mean the divine.)

And that, for me, is important. Our sense of self, of who we are and how we love and live, is a complex mystery that has many dimensions: physical, emotional and spiritual. So to keep a balanced sense of self, we need to attend to each… and for that reason I’m thankful that these three writers have all crossed my radar.

Comments

3 responses to “All In The Mind? Thoughts on Identity and Neuroscience”

Interesting, must look out The Echo Maker, I wonder if Capgras Syndrome was the inspiration for the plot of Total Recall?

Interesting idea. There’s definitely some great neurological ideas going on in that film – and others. Echo Maker def worth a read.

An interesting companion piece to those three ight be Antonio DAmasio’s Self Comes to Mind–great book about identity and consciousness–he’s head of neuropsych and science at USC–provocative book in the field—am working on some October events for you, really looking forward to seeing you, b